“Things are getting more efficient, and people don’t like that.”

Paraphrasing Matt Levine, as markets get more competitive, the historical sources of margin disappear as new entrants attempt to extract smaller pieces of the same pie. In the old days, Twitch and YouTube were the only platforms competing to sign top streamers. You could think of them as an oligopoly - obviously they were competitive with each other but they were incentivized to not pay that much for streamers:

Fairly good information about what the counterparties are paying for streamers, which allows them to set markets similarly

Streaming was big but no one streamer had so much power that they could move the market themselves

Oligopolistic institutions can exert monopoly pricing power.

But if you’re reading this newsletter, you know there’s so many more platforms today and one way to think about them is that they have VC money to burn and attract creators in the pursuit of growth, and are irrationally bidding up prices. On the other hand, with more creators and more platforms and a gradually fragmenting market, the rational expectation is that the prices being paid for creators actually represent closer approximations of how much creators are worth to a platform.

Anyways platforms are paying a lot for streamers now. Nobody’s grumbling externally but Amazon (always) and Google (in the age of Porat) are not exactly free-spending machines anymore.

And people are watching non-gaming streams more than gaming streams (well, on a per-category basis).

How do you financialize a song?

Here’s a super interesting profile of a music investment fund. One way you could think about them is that they’re trying to be an index fund of all popular songs, similar to how the S&P indexes “all” the “popular” companies. However, unlike stock market funds, this one is in a market which is zero-sum and low liquidity.

“Hipgnosis’s recent interim results showed how skewed revenues from downloads and elsewhere are towards a small number of songs: 0.5% of the portfolio accounts for 43% of income.” — this is probably true for the entire song market; extreme volatility suggests you should buy the entire market to avoid missing out on hits.

Perhaps the most interesting paragraph to me is:

When Spotify launched in 2008, Mercuriadis became intrigued by streaming music. Central to Spotify’s user experience was the ability to create personalized playlists by culling songs from all genres and artists. The start-to-finish thread of a full album was becoming less important to streaming adopters. In decades past, he observed, the majority of artists wrote their own songs. Kurt Cobain wrote all the lyrics and much of the music for Nirvana’s 1991 album, Nevermind. Contrast that with Adele, who worked with 10 different songwriters for her 2015 smash, 25. “It became clear to me that the power was shifting from the artist to the songwriter,” Mercuriadis says. “But the songwriters weren’t in a position to reap the benefits.”

The market for music has become fragmented and driven not by full albums but individual singles and songs. That focus decentralizes power and ownership from the artist to songwriters, producers, and all the other parties. The other maxim this paragraph reminds me of is “there are only two ways to make money: bundling, and unbundling.” Albums were a form of bundling a few good songs (the singles) with a bunch of filler to cover roughly 48 minutes of music. Mixtapes, and now Spotify, are a form of unbundling. The overall coherence of an album from start to finish is now a lot less important, compared to having smash songs.

In fact, I’d argue that it’s probably not important to have a hit song, so much as it’s important to have a hit hook or a hit line. “High Hopes” comes to mind - not a particularly great song as a whole, but a catchy chorus and it got picked up as a meme. Most of the recurring money in music now comes from using the song in an ad or a movie and not so much from streaming, at least which flows to songwriters (I’m not sure how live performance/merch income comes into play, but presumably more of that goes to performers).

Sean Carter once summed this entire business up as,

So yeah, I sampled your voice, you was usin' it wrong

You made it a hot line, I made it a hot song

And you ain't get a coin, nigga, you was gettin' fucked then

I know who I paid, God – Serchlite publishin'

I’m just waiting for a rapper to similarly call out a “private equity song fund” in a diss track.

Subscriptions are eating apps

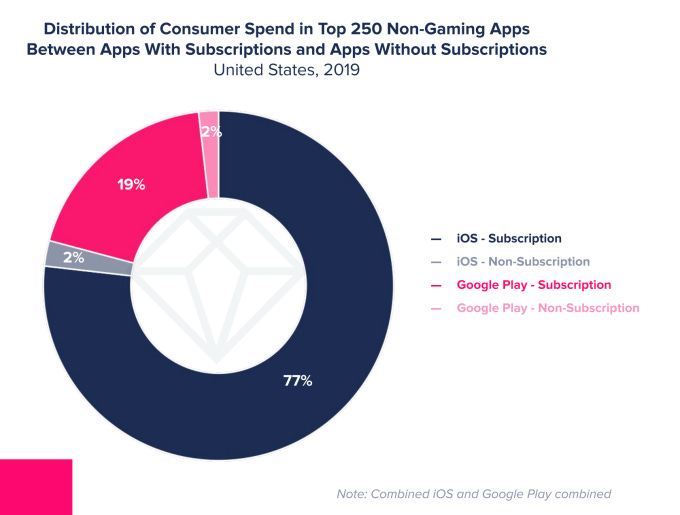

App Annie released a report on the state of the app market, and it’s super interesting and worth a read through, but let’s only touch on the subscription related parts.

Subscriptions are now the primary way many non-gaming apps generate revenue. For example, 97% of consumer spending in the top 250 U.S. iOS apps was driven by subscriptions, and 94% of the apps used subscriptions. On Google Play, 91% of the consumer spending was subscription-based, while 79% of the top 250 apps used subscriptions.

In particular, dating apps like Tinder and video apps like Netflix and Tencent Video topped 2019’s consumer spend charts, thanks to subscription revenue.

It’s worth noting that most of the spend is likely driven by apps like Tinder or Netflix with extremely high margins, and that most of this spend isn’t going to individual creators. App stores tend to take 30% cuts of revenue from the subscription (for the first year, and typically a decreased rate the next year). Companies like Patreon or Substack take only 5-10% of revenue, which makes it untenable for them to create apps.

Actually, I just learned that Patreon has an app, but it seems to be extremely bare-bones and basically a WebView over the home feed, without the ability to subscribe, and without discovery, because discovery is not part of Patreon’s ethos. So I stand by my previous statements.

What I’m reading

The Sellout, by Paul Beatty

The Ecstasy of Communication, by Jean Baudrillard

The Wind-Up Bird Chronicles, by Haruki Murakami